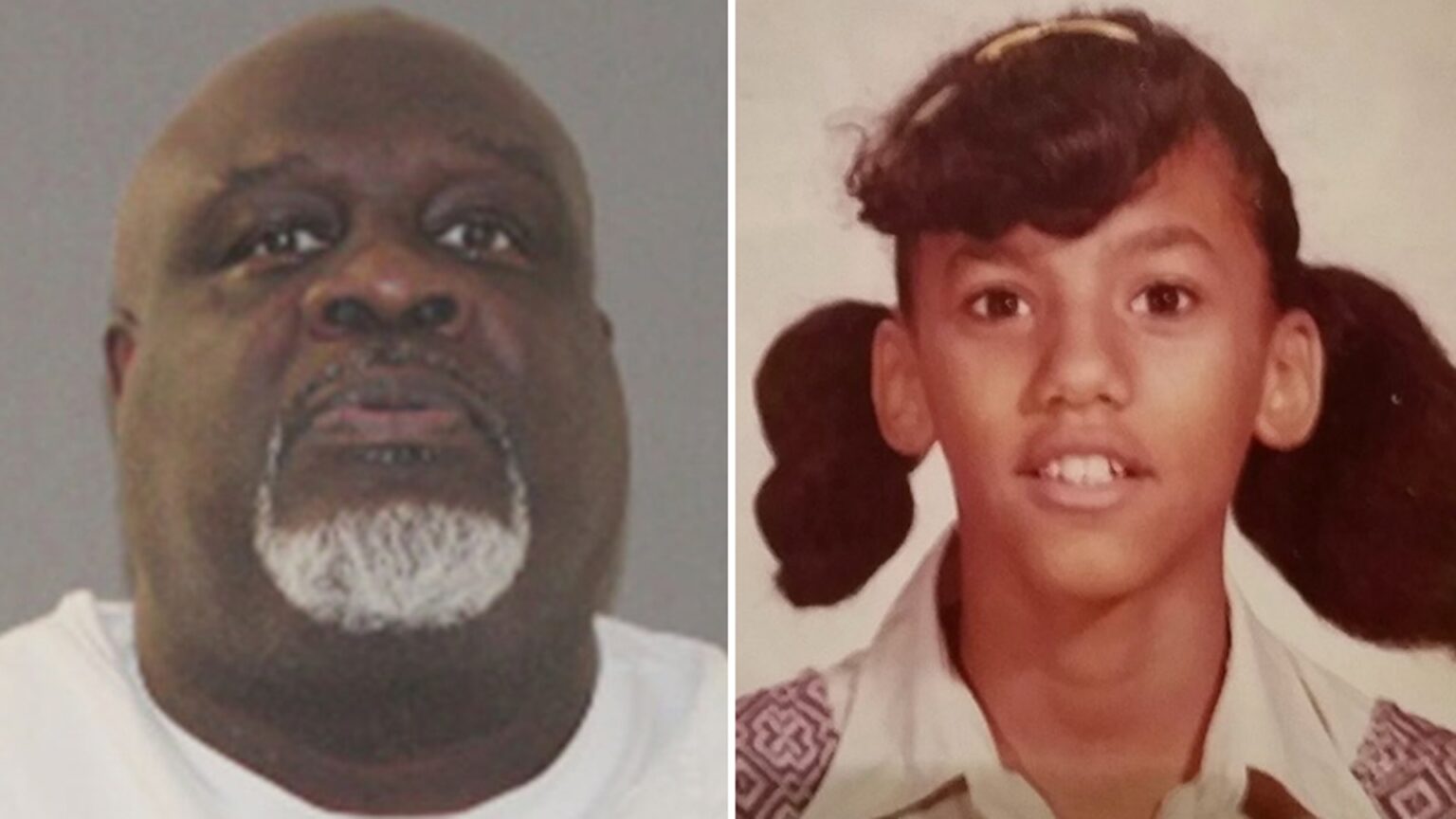

On a somber evening in Huntsville, Texas, the state executed Garcia Glen White, a 61-year-old man convicted of the brutal 1989 murders of twin teenage girls, Annette and Bernette Edwards, in their north Houston home. White’s execution by lethal injection came after more than three decades of legal battles and years of anguish for the victims’ families, who, after countless appeals and delays, finally saw justice carried out.

The twin murders sent shockwaves through Houston, especially within the Edwards family, who were left devastated by the horrific loss of their two daughters. Annette and Bernette Edwards, only 16 at the time of their deaths, were the victims of a heinous crime that unfolded in the midst of a drug-related dispute between White and the girls’ mother, Bonita Edwards. Over the years, White’s case became one of the many emblematic of Texas’s death row system, marked by protracted appeals, emotional pleas from victims’ families, and mounting legal and moral questions about the use of the death penalty.

The Tragic Events of 1989

The gruesome slaying of the Edwards twins took place on a hot Houston summer night in 1989. The two girls were home when White, a known acquaintance of their mother, entered their house in the heat of an argument that allegedly stemmed from drug-related disputes. The details of the crime, which authorities would later piece together, painted a picture of unimaginable violence. Both girls were found murdered, with evidence suggesting they were victims of a rage-fueled attack that ended their young lives in a horrific manner. White’s motive was believed to be linked to drug dealings with their mother, and evidence suggested one of the girls may have been sexually assaulted before her death.

At the time of the murders, White was already a figure of interest in other unsolved cases, including the killing of a neighbor, Greta Williams, whose body was found rolled up in a carpet, and the 1995 murder of Hai Van Pham, a convenience store clerk. Despite his apparent involvement in these additional homicides, White’s initial conviction came solely for the murder of the Edwards twins.

White’s criminal record, combined with the brutal nature of the killings, led to his conviction in 1996. He was sentenced to death by a Texas jury, a decision that would set in motion a nearly 30-year legal battle to keep White alive through appeals, challenges, and petitions from his legal team, even as the victims’ families waited agonizingly for the day justice would be served.

A Life Spent on Death Row

After White’s conviction, the lengthy process of appeals began, reflecting the often drawn-out nature of death penalty cases in Texas and across the United States. White’s legal team, led by defense attorney Pat McCann, worked tirelessly to keep him from facing the ultimate punishment. Over the years, White’s attorneys raised numerous legal challenges, including arguments about his mental competency, claims of intellectual disability, and efforts to overturn his death sentence based on procedural errors and new evidence.

These legal efforts, while consistent, were largely unsuccessful. The courts repeatedly upheld White’s death sentence, citing the brutal nature of his crimes and the strength of the evidence against him. However, this did little to ease the anguish of the Edwards family, who endured decades of delays and postponements as they waited for closure. The impact of these delays on victims’ families is often overlooked, yet it profoundly affects their ability to grieve and move forward.

As White sat on death row, he became somewhat of a loner, spending his days in isolation, reflecting on his crimes, and awaiting the inevitable. Texas Department of Criminal Justice records show that White was a quiet, reserved inmate who mostly kept to himself. However, in his final days leading up to his execution, White began talking with other prisoners and reflecting on his life choices. He spoke to a few visitors and reportedly spent his last night awake, packing his belongings and praying for peace.

The Execution

On October 1, 2024, White was led into the execution chamber at the Huntsville Unit in Texas. The stark reality of the moment was palpable as the prison staff prepared to administer the lethal injection. As White lay strapped to the gurney, with intravenous lines connected to his arms, he was given the opportunity to deliver his final words.

“I’m sorry for all the pain I caused anyone,” White said in a soft voice. “I just ask you to please find comfort and closure in your heart.”

He then surprised those present by singing a gospel hymn, tapping his restrained hand and foot in rhythm to the song. It was a rare moment of personal expression in the final moments of his life. He also thanked the prison guards for “treating us like human beings,” showing a brief moment of gratitude in a situation that otherwise brimmed with tension.

No members of the Edwards family were present to witness the execution. According to officials, the family had chosen not to attend, likely due to the emotional toll of the decades-long legal proceedings. White’s attorney, Pat McCann, explained that White had made the decision not to have any family or friends present during his execution. As a result, White died alone in the execution chamber, under the watchful eyes of prison officials and the relatives of his other victims, Pham and Williams.

The lethal injection was administered at 6:39 PM, and within minutes, White’s breathing slowed and then stopped. He was pronounced dead at 6:56 PM. The quiet end to White’s life marked the conclusion of a long and painful chapter for the families of Annette and Bernette Edwards, as well as for the families of his other victims.

Decades of Legal Battles

Garcia Glen White’s case became a focal point for discussions surrounding the death penalty in Texas. Over the years, his legal team mounted several last-minute challenges to his death sentence, citing various reasons, including claims that White suffered from an intellectual disability. McCann argued that White had a cognitive impairment that should have disqualified him from execution under the U.S. Supreme Court’s rulings prohibiting the execution of intellectually disabled individuals. The courts, however, were not swayed by these arguments, and White’s appeals were repeatedly denied.

In the final hours before White’s execution, his legal team filed a flurry of appeals, seeking to delay the lethal injection once again. But the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected their arguments, calling them “too late and lacking in merit.” The U.S. Supreme Court also turned down several last-minute petitions, paving the way for White’s execution to proceed.

District Attorney Kim Ogg, who was present for the execution, met with the families of Pham and Williams before the execution and expressed her condolences. After the execution, Ogg addressed the media and urged for reforms to the appeals process for death penalty cases, which she argued had become unnecessarily prolonged. “If you’re going to have the death penalty and continue to execute people in Texas, we have to do something to help these families get to the end,” Ogg stated, underscoring the need for more timely resolutions in such cases.

The Legacy of Garcia Glen White

The case of Garcia Glen White is one that touches upon numerous aspects of the criminal justice system, from the death penalty and its ethical implications to the lengthy appeals process and the emotional toll it takes on victims’ families. For the families of Annette and Bernette Edwards, justice may have been delayed, but it was ultimately delivered, bringing some semblance of closure after years of waiting.

White’s case also reignited debates over the death penalty in Texas, a state that continues to lead the nation in executions. Proponents argue that justice was served for the heinous crimes White committed, while opponents question the morality and efficacy of the death penalty as a form of punishment. Regardless of where one stands on the issue, Garcia Glen White’s execution marks the end of a legal saga that spanned more than three decades, leaving behind a complicated legacy of pain, justice, and unanswered questions.